From Abia to Abeokuta, disability-insensitivity permeates 2025 budgeting, signalling failure of a policy President Tinubu’s aide tried to push on his steam alone

By Elijah Olusegun

When Mohammed Abba-Isa, the senior special assistant to the president on disability, took his own assistants and chief of staff on an Abuja-Lagos flight February last year, he convinced himself he had a mission. More so that he could drop President Bola Tinubu’s name to get some eyeballs at the Alausa Government House for his pet project.

It's over a year now since Abba-Isa made the dash. And the initiative, the Governors Disability Connect, has proved a non-starter. No governor has connected with Gov. Babajide Sanwo-Olu he made the initiative’s ambassador.

It’s no surprise.

From the start, the ambassador himself never considered the initiative and its launch worthy of his time. It was the state’s ministry of youth and social development officials, including some from LASODA, who spared time to hear what Abba-Isa had to say: that Sanwo Olu should help convince his colleagues across the nation to club together, and “build a national consensus on PWD-friendly policies and environmental conditions”. In the policy design, another body, including the NCPWD, will sit in judgement, wielding some six Key Performance Indices: budgeting, procurement, development plans, governance, legislation, all disability-sensitive, and a disability commission to the bargain.

Abba-Isa got what the Alausa crowd thought he needed to hear during the launch. “The administration of Gov. Babajide Sanwo-Olu has championed the cause of PWDs by ensuring over 400 of them are absorbed into the state civil service, as well as being given fair shares in the health and the education sectors,” said LASODA General Manager Adenike Oyetunde-Lawal.

ER reached out in February to disability commissions in some states to follow up the development—if Sanwo-Olu has on-boarded their governors.

Oyo’s Disability Commission Director-General Ayodele Adekambi and his Abia counterpart David Anyaele said their bosses have had nothing to do with Sanwo-Olu on any disability initiative. And Anyaele wouldn’t chime in any opinion on what he didn’t know.

Adekambi, however, dived in. “Oyo state’s disability commission has the highest 2025 budget in Nigeria, even higher than Lagos’,” he said. For the disability-friendly environment, the state’s ministry of environment, according to him, will soon provide road and park markers for PWDs for use in private and public transport systems across the state.

Oyo seems an exemption.

Abia remains unconnected still, as disability-friendly budgeting goes. Anyaele flew off the handle when ER asked him about his commission not featuring in Abia’s multi-year budget 2025 to 2027. “This is falsehood taken too far,” he said. “I don’t know who is dishing out this falsehood to you. If you continue like this, I will stop responding to you.” His worry about the intention of the enquirer overwhelmed him. He refused to confirm or deny ER’s enquiry about his commission’s N455 million budget (besides climate and nutrition tags of N45 million), and how disability-sensitivity the state budget is.

The Centre for Citizens with Disabilities (CCD) founder turned political appointee probably had his demon ER’s request for clarification triggered. Or he was hiding his ignorance and lack of capacity to help his state and his eight-month-old commission prepare a disability-sensitive budget. His ignorance, however, stood out. ER requested for a copy of his commission’s budget to counter the ‘falsehood”. He raged, again, for not inquiring from him first before concluding in the request for clarification. “I won’t give you,” he said. The approved copy of the budget document has been publicly available, though. On the document’s pages 28, 58. 156, and 259, the supervising ministry of youth and sports development voted the commission N455 million (0.06 percent of Abia’s N750-billion budget)—to fund 35 projects in capital expenditure, and to also cover recurrent expenses. Over 30 percent of the capital projects is buying office items including HVAC and electronic appliances, all tagged “office furniture”. Other line items include orientation, ceremonies, and welfare services. Even the commission itself is a line item under the capital spending totaling N259 million.

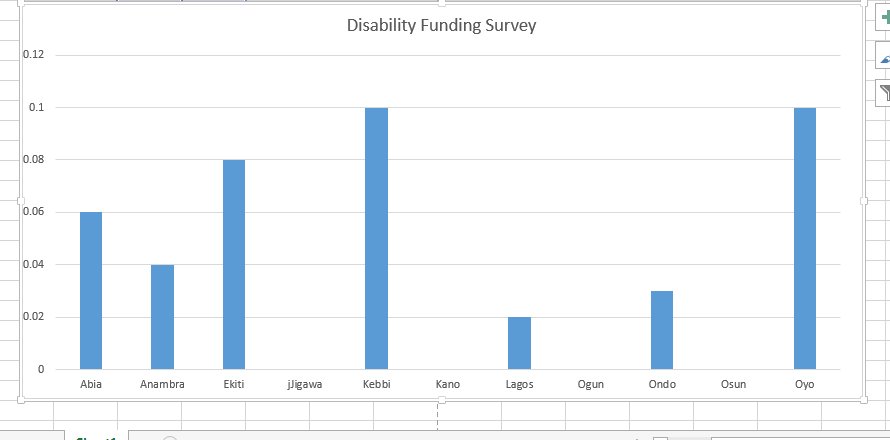

Anayele’s combustion, no doubt, created a smokescreen for disability-insensitivity and opacity in government budgeting in Abia. But his state is not alone in this. Nothing smacks of disability-sensitivity in the analyses of many of the 2025 budgets for Ogun, Oyo, Anambra, Osun, Ondo, Ekiti, Kano, Kebbi, and Jigawa. And, even, Lagos, the so-called champion of disability.

Of the 11, only Lagos, Oyo, Kebbi, Ondo, Abia, and Ekiti, all having disability commissions, got their separate budgets from their supervising ministries. Under the humanitarian affairs ministry, Kebbi’s disability commission got N830 million, 0.1 percent of the state’s N580 billion this year. Lagos voted N756 million of the state’s N3.4 trillion-budget to the Lagos Office of Disability (LASODA). That is 0.02 percent, compared to last year’s N1.2 billion (0.52 percent) of the N2.3-trillion budget. Oyo, however, allocated N1.2 billion (0.1 percent) of its N1.2 trillion to its disability commission this year. Ondo sliced its disability commission N216 million (0.03 percent of its N695-billion budget) in recurrent expenditure only. No capital expenditure in both states. Ekiti voted its disability commission, under the women affairs ministry, N309 million, 0.08 percent of the state’s N375-billion. Anambra’s disability commission, under social welfare, children, and women affairs ministry, got N218 million in total expenditure—0.04 percent of the state’s N606 billion.

Other states without disability commissions have no paper trail of budgeting for disability. Ogun allocated no funding for disability in any form one can trace in the over N1-trillion budget. But allocations to ministries like sports and special needs (Osun), women affairs and social development (Kano and Jigawa, over N7 billion each), humanitarian and poverty alleviation, and agencies like Ogun CARES hint of disability getting trickles from the flows. Osun, for instance, allocated N5.1 billion (of its N428 billion) to the ministry of sports and special needs that tags disability along.

Abba-Isa didn’t respond to ER’s two separate requests for what he had to say about the other governors giving him and his brainchild a cold shoulder. Nor did he give his take on the sustained insensitivity to disability in most of the states’ 2025 budgeting.

If he had looked hard enough while embarking on the journey, the road bumps along the policy route could have forewarned him. First, it is above Abba-Isa pay-grade, as a presidential appendage, to one-up the NCPWD, and make such a policy move. Not even on issues of disability Nigeria’s policymakers consider second-rate. His predecessor Samuel Ankeli made no such move, despite the administration he served passing the Discrimination Act 2018 to law. Again, the pettiness of Abba-Isa motivation took the shine off the initiative. According to his Chief of Staff Yusuff Iyodo, Tinubu comes from the APC state. “Essentially, we expect Lagos to be an ambassador of the programme,” he said during the launch. That somewhat leavened up the policy with partisanship.

So his ambassador Sanwo-Olu couldn’t have the right motivation to run with. Getting his foot in his neighbor Makinde’s door to make the hard-sell then became a grind.

Nothing prevents any governor and their disability commission from latching on to the power play to excuse their apathy to disability. And, by so doing, they ring the death knell for the policy. Adekambi agreed Abba-Isa came up with a good initiative. “[But] they are APC; we are PDP,” he told ER. That us-versus-them game Abba-Isa teed off will go on in the 12 states the PDP governs.

Naturally, though, the governors have no excuse—whether Sanwo-Olu motivated or bundled them into the Disability Hall of Fame, Abba-Isa’s idea of recognizing the most disability-sensitive governor. Analysts say the national and state disability laws in Nigeria can mainstream inclusion, access, and development; the governments only have to abide by the provisions. “Unfortunately, many of these concerns are not front-burner conversations yet in Nigeria,” Adenike told ER in a recent interview. The situation probably tempted Abba-Isa to go out on a limb on the quest to become a policy hero.

His tight upper lip suggests the journey has turned a misadventure. He barely cares about the initiative now. LASODA, whose GM didn’t respond to ER request for updates on Sanwo-Olu’s effort, may have forgotten about it, too.

Maybe Abba-Isa's faith wavered somewhere along the line. Or the hurdles came in quick succession. Whatever happened, the half-a-dozen Sanwo-Olu men, the only government officials in Nigeria familiar with the Disability Governors Connect, won’t take Abba-Isa seriously again. Nor will observers in the disability community ever again regard any policy brainwave coming from a backroom at Aso Villa.