Table of contents [Show]

- Lagos rakes up a few children with disabilities, leaves them to swim or sink, and takes credit for leading inclusion in Nigeria

- Fatima’s been taking her daughter to the New Oko Oba Primary School Inclusive Unit for three years. She initially hoped the Lagos government’s promise to leave no child behind would come true. Now she wonders if there exists somewhere else farther behind.

- Alice crumples in her wheelchair parked in front of the last row in a class of about 50, all with disabilities. The floor above her holds another class in the multistory building whose roof has been partly peeled away, funneling down most of the November rains. It’s the only school with an inclusive unit in that soulless nook of the state’s education District 1.

- “Hello, Comfort!”

- Fatima walks up to her daughter, and wipes a length of saliva dribbling down the girl's mouth. The class teachers, a man and a woman, look on.

- “You, don’t splash your spit on my girl.” She waves her thick index finger at a girl. A section of the class erupted in rigid laughs. They enjoy such mini-drama whenever Fatima spends time with them.

- She chats with the teachers for a moment, and then breezes out of the class. Her steps ripple with vigour as she leads the way to a viewing centre for an interview for this story. She will later return around 1 pm to feed Comfort, clean her, and lift her out of the school gate before wheeling her home. Fatima does all these daily. For three years now.

- Eight parents among about a dozen interviewed for this report stay at their children’s schools weekly or twice weekly, caring for them, especially the children with intellectual disabilities and development (CWIDDs). The kids have cerebral palsy, spinal bifida, intellectual impairment, and other disabilities that make them demand greater attention.

Lagos rakes up a few children with disabilities, leaves them to swim or sink, and takes credit for leading inclusion in Nigeria

By Segun Elijah

Fatima’s been taking her daughter to the New Oko Oba Primary School Inclusive Unit for three years. She initially hoped the Lagos government’s promise to leave no child behind would come true. Now she wonders if there exists somewhere else farther behind.

Alice crumples in her wheelchair parked in front of the last row in a class of about 50, all with disabilities. The floor above her holds another class in the multistory building whose roof has been partly peeled away, funneling down most of the November rains. It’s the only school with an inclusive unit in that soulless nook of the state’s education District 1.

“Hello, Comfort!”

Fatima walks up to her daughter, and wipes a length of saliva dribbling down the girl's mouth. The class teachers, a man and a woman, look on.

“You, don’t splash your spit on my girl.” She waves her thick index finger at a girl. A section of the class erupted in rigid laughs. They enjoy such mini-drama whenever Fatima spends time with them.

She chats with the teachers for a moment, and then breezes out of the class. Her steps ripple with vigour as she leads the way to a viewing centre for an interview for this story. She will later return around 1 pm to feed Comfort, clean her, and lift her out of the school gate before wheeling her home. Fatima does all these daily. For three years now.

Eight parents among about a dozen interviewed for this report stay at their children’s schools weekly or twice weekly, caring for them, especially the children with intellectual disabilities and development (CWIDDs). The kids have cerebral palsy, spinal bifida, intellectual impairment, and other disabilities that make them demand greater attention.

Say no evil

The Lagos State Universal Basic Education Board (LASUBEB) and its Inclusive Education unit won’t respond to interview requests for this report. Head of the unit Omolua Hilda asks not to be bothered, and directs requests to chairman Wahab Alawiye-King. Public affairs head, Enitan Adewumi, also refuses to respond to text messages and phone calls.

Three teachers, one of them a contact person for her school, and two headmistresses, among the staffers of seven inclusive primary schools visited, also refuse to talk. They demand a letter of authorization before they can talk—about staffing and other issues in their inclusive units.

Tight lips notwithstanding, one teacher to over 40 children with disabilities (CWDs) in a class in many of the state’s 33 primary inclusive units hits nobody as adequate.

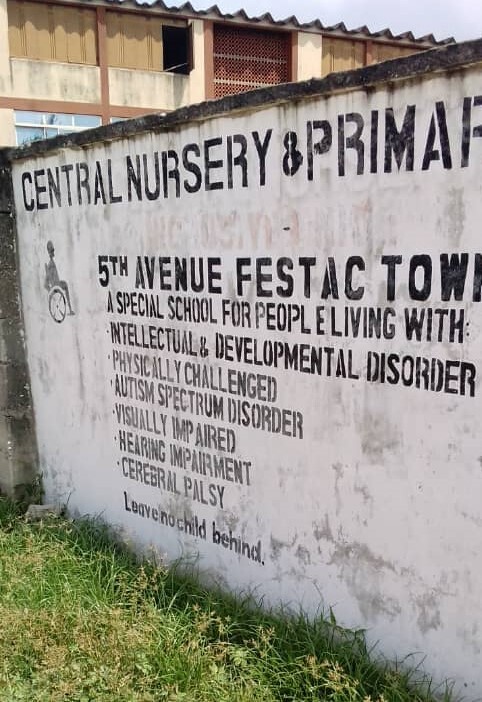

Mapping and Assessment of the 44 Inclusive Primary and Secondary Schools in Lagos, a report sponsored from the Netherlands, says there’s some progress. That’s when compared to how it all began in 2003. The state, then, tinkered with a policy for educating kids with disabilities. The report authors, the Festus Fajemilo Foundation and its collaborators, however, identify, among other findings, a problem: staff strength.

The World Bank also did in 2020.

But Alawiye-King always boasts of the marvels the Inclusive Education policy has done in the grip of the state government. “Lagos State does not only fulfill this right [of adequate catering to CWDs], but runs a blanket system through its inclusive education policies which ensure no child is left behind,” he said during a meeting in the thick of covid-19 pandemic.

Mothers mad at make-believe

Fatima and other parents, however, insist Lagos inclusive education, with its hype, is a non-starter, because it has no support staff, among others things it lacks; and it has succeeded only in consigning the children to backwardness. With no training or formalities, parents, frustrated, now take up caregiving at schools.

“They no longer regard disabled people as humans.” Fatima’s voice rises as she garbles her words.

Miles away at the Igando LG Primary School, Alimosho, another mom, in her 60s, has angrier words for the policy, its makers, and the school authorities. “They are doing nonsense,” Mrs. Fatila says. The trader blames her inability to take Ahmed, 22, to a private school where she believes children like him can benefit better from education. Her regular slanging match at the inclusive unit has got her so many eye rolls, but she doesn’t care. “That place, I will say it, they’re not doing anything.”

Lagos will argue it led the pack in adopting the policy in 2015, three years before the federal government articulated its own. Four years before then, it enacted the Lagos Special People Law, with its free basic and compulsory education for every child. The act also established the Lagos State Office of Disability Affairs (LASODA) to coordinate things across all the ministries. But today, about 10,000 CWDs are able to attend school (only a third of that enrolled in public schools); more than 20 times that number, the report says, beg or waste away out of school. The state pretty much fell short of the Education For All target, part of the MDG 2015 for which it made the policy and the law.

Lagos is still failing, with almost two decades of experience plying the policy. Here inclusive education means lumping a crowd of CWDs in a class, with one or two teachers, including those with disabilities. “There’s no standard operating procedure,” FFF’s Director Festus Fajemilo tells ER. Before his foundation and others developed a cookbook on cooperative teaching (pairing a regular teacher with a special education teacher) for them, those schools, he says, just did what they liked. They still do. Only three schools in District 1 has a semblance of inclusion, of all the primary and secondary schools—in addition to five special schools—across six education districts in 20 LGAs and 37 LCDAs. District 5 has the highest number of such units: seven. District 1 comes second, with six units. Districts 4 and 6 have two and three units respectively.

Lonely moms of helpless pupils

Looking at their classrooms, access, teaching aids, and other facilities, it’s clear the units cater to CWDs whose parents are market women, artisans, and other Lagosians, about two million in all, living in urban poverty. Plus a particular class of Nigerians: the victims of circumstances.

“Most of the parents of children with intellectual impairments are like me,” Fatima says. Her husband skipped out on her and the girl 15 years ago. Because she refused to heed his order to throw Comfort away when they discovered she has cerebral palsy. He has never looked back since then. “My own people, too…. They abandoned me because I refused to dump the girl somewhere.”

Statistics of kids with CP, Down syndrome, spinal bifida and others leading to intellectual impairment comes second to those with hearing impairments across all the districts. Twenty-two of the 33 primary schools take in those with hearing problems along with other impairments; 19 enroll those with intellectual difficulties alongside others. The nature of these enrollees piles up the burden of caregiving, among other support services these classes of CWDs need, which there’s no staff to shoulder.

Both, for instance, need audiologists and speech therapists. Lagos employs no single audiologist in all the 44 inclusive units. It has only three speech therapists. The National President of the Association of Intellectual Disability and Development of Nigeria (AIDDN) emphasizes this dearth of support staffers. Joko Omotola, whose child is a member of the association, can’t stand the parrot-like fashion the state toots the no-child-left-behind trumpet—when support staffers are not available for the poor attending inclusive schools. According to her, she takes her child there in the morning, and comes back for her in the afternoon. “Nothing more to the glorified daycare centre.”

For many of the parents, the daily school run comes at a high cost. A parent around Ogba in the education district 2 says she commutes daily, swaddling her five-year-old son with physical disability to the Amosun School Complex, Agege, in District 1. “All Saints at Oluwole is closer,” she says, “but I prefer here because they have teachers who love children.”

As of 2020, Amosun employed only one teacher. Now with more than 50 pupils, the unit boasts of three: one with hearing impairment, her colleague, and the unit head. They combine teaching with support services, at least caregiving.

Another parent there also commends the teachers’ loving care. She narrates watching the headmaster one day caring for a grown-up boy who soiled himself. “I pitied the man. I could only help him look for water while he removed the boy’s clothes,” the petty trader and mother of a child with Down syndrome says. Her son, about 13, keeps rocking and bobbing and grinning with a cupped hand under his chin as they walk home. He has been attending the unit for years. “That’s the only thing he knows how to do,” she says, “at school, in the neighbourhood, all over Agege.”

The two mothers note older pupils assist, too, in caregiving at Amosun. The role appears the easiest anyone can play. Not necessarily so.

Most of those the inclusive units employ as caregivers are cleaners. “And parents at the PTA have warned that only those who have children with disabilities should be employed for caregiving,” Fatima says. It’s a field on its own. She went to school to earn a certificate in it, and the association later employed her as a caregiver. “I stopped collecting salaries from the association. I wanted to do it free.” She applied to SUBEB four years ago, hoping they employ her so she could devote more time to other kids who need support like her daughter. She can handle all their slobbering and accidents and demands. Lagos ignored her. The school later took on a cleaner—a hireling who bothers only about sweeping and cleaning and pay. “A caregiver knows what a child needs even before the child asks,” Fatima says.

More than two-thirds of both inclusive primary and secondary schools in Lagos lack such caregivers. The FFF and others confirm it. Even the last resort, cleaners, has become a luxury: seven in all the inclusive primary schools and none in the inclusive secondary schools.

Policy primed to fail

Lagos wouldn’t have done anything stellar with a policy and a law brimming with provisions, but wanting in action—action backed with finance and political will. Alawiye-King, at any opportunity, riffs on the leave-no-child-behind mantra. Or some statement like: We’re doing all we can to ensure our special-need children have access to qualitative basic education.

That’s still all talk. The state fails to put its money where its mouth is.

The policy skips provisions for line item budgeting for inclusive education. Of the N.9 trillion Lagos budgeted last year, N146 billion went to education. A Lagos inclusive education funding document, which a limb-focused NGO Irede Foundation put together, shows amounts the state allocates to education have been increasing for years. Yet N53 million went to LASODA where allocations, largely for bread and butter and bills, then trickled into inclusive education and its 870-man staff. The office is incompetent, Lukman Salami, chairman, the Nigeria Association of the Blind, Lagos chapter, tells ER. And it survives on special grants, in the region of half a billion naira yearly. But neither the state’s ministry of education nor SUBEB prepares a separate line item budget for inclusive education.

It should be expected. The finance ministry is one critical stakeholder missing among the seven, including the ministry of environment, the policy co-opted into implementing inclusive education.

And for the Special People Law, none of its eight provisions addresses budgeting and financing for inclusive education. They all double down on advocacy, coordination, compliance, and certification.

A coalition of CSOs, the Lagos State Civil Society Partnership, made a point of direct budgeting for inclusive education two years ago. Folashade Adefisayo, the education commissioner, promised them the state would look into it. Nothing has happened since then. SUBEB and its Inclusive Education office refuse to respond to interview requests for clarification.

Almsgiving no inclusion

Many say this unwillingness still boils down to the charity model governing disabilities in Nigeria. Elected officers tossing the PWDs crumbs seems easier than legislating for PWD’s direct inclusion in Lagos budgeting. And almsgiving appears humane enough—with a lot of street-cred and other benefits for politicians who dare. Mrs. Fatila reels out names of politicians who show kindness regularly to Ahmed’s former school, the Ore-Ofe Inclusive Unit, Dopemu, in District 1. They gave him uniforms, books, noodles and drinks. “Nobody from the local government helps them here at Igando,” she says.

When they give, politicians stamp their fingerprints on the receiving schools—either as philanthropy or constituency projects. At the All Saints Inclusive Primary School, a toilet the Lagos House of Assembly Speaker Idowu Obasa (Foundation) built for them stands out, not yet commissioned. A father of a girl with intellectual development tells ER while narrating how CWDs defecate around the school. The foundation also handed out boons to kids at Amosun in Nov., 2021, saying it was about the Speaker’s large heart.

Doling out what the CWDs deserve to them as alms doesn’t look like good-heartedness to the parents. It’s wickedness, Fatima says. ‘They have children with disabilities, too. It’s not like they don’t have. They treat our children like beggars, and send their own abroad.” Fajemilo, whose son has spinal bifida, says at least eight support professionals, including psychologists, therapists, work with pupils in inclusive classrooms abroad. They don’t leave all that to charity.

Lagos leaves them farther behind

So far, these good deeds haven’t solved the support staffing problem crippling the kids’ learning curve in Lagos. “I don’t see any future for my daughter in the so-called ‘special children’ school,” Fatima says. “I’m just happy she’s alive.” Comfort, adolescent, is still in primary three. “All I wish for her in life is to be able to sit up, and feed herself.” Fatima stares ahead, at nothing, as she talks. Other parents also confess, with resignation, they have no lofty expectation for their children in life. Most admit the children are not progressing. The chairman of the National Association of Special Education Teachers in Lagos agrees on the poor staffing of inclusive schools in the state. But on the kids not progressing, Oyebade differs. He denies this even when reports confirm enrolment at vocational centres, completion and promotion rates from inclusive public primary schools to secondary schools keep falling. (Unlike the success stories in special children schools.) “How do you measure the progress of pupils who can’t talk? Or children with intellectual impairments taught by a blind teacher? ” ACWIDD’s President Omotola says.

Some of the parents claim they see improvement in their children’s learning. But they can’t point at anything in particular—apart from some of the pupils singing and dancing all day, or struggling to count from 1 to 10, or trying to remember their surnames. “Our children don’t need all this 1, 2, 3, they teach them,” Omotola says. Most of the CWIDDs, their parents say, are between 13 and 22, and are still near the beginning in elementary schools. “The ‘special school’ is just a place to keep him so I can go out,” Fatila says of her son. Ahmed, in primary 3, has soiled himself four times in class so far. No one cares about him since his first teacher and caregiver (voluntary) moved up the school’s food chain last year. The mother takes him to school daily, and, at times, helps in sweeping his classroom. The class used to have a cleaner. Its surrounding lies in dirt now, and the school’s only toilet spills over with excreta, she says. Her son doesn’t like it. If Ahmed can’t hold it in again when he has a bowel movement, and nobody understands the pressure, he takes a dump—in his shorts. His teacher kept him like that till closing time the last time it happened. “The excreta streamed out of his knickers down to his sandals; it dried up and crusted in his…,” she says. “They wouldn’t clean him up, or call me. Neighbours saw the embarrassment, got angry, took pictures, and brought him home.” At the All Saints Inclusive Primary School, if such accidents happen, the teacher simply quarantines the pupil. “They’ll call you to come and clean up your child. They tell you they’re teachers. Not cleaners,” a parent says.

A cycle of poverty

Some mothers leave not only their phone numbers for teachers to call; they also abandon their petty trading to stay with their children in classrooms. Mrs. Adeniran enrolled her son with spinal bifida in the inclusive unit of a secondary school in Bariga. Because it has no care staff, the school allows her to stay with her son on the two days she can afford transporting him to school. “We are seven like that—staying with our children in the school to give care,” she says. The school keeps the mothers in a separate classroom.

Staying with her son twice weekly costs Adeniran trading hours. On top of that loss, she can’t pin down any progress the son is making. “He’s not learning anything (he fell sick recently), but they say we should try and give him opportunity to attend school.” She loses about N10,000.00 each day she misses selling her petty things.

Single moms of CWIDDs, when it comes to the bottom line, lose more than others CWDs’ moms. Fatima complains of the financial toll: buying diapers her daughter uses daily, medications, feeding, transportation, and others. “And I can’t leave her for any job for long hours—even if the pay is big.” Paying her one-room rent got difficult at a point. She had to take the girl along to ask a local government chairman for help. “Because I am not a party woman, I kept getting ‘come back later’—until I decided to cut him off,” she says. She’s now taken up a night-shift job at an old people’s home, spending the day to care for Comfort at school—where she learns nothing.

These opportunity costs, for CWD’s moms, and the learning problems their children experience usually lead to deeper poverty. More so in a market-driven economy that excludes people with no skills. Studies confirm the costs of the exclusion range from 3 percent to 7 percent of a country’s GDP.

With single mothers now leaving their jobs to care for their CWDs in Lagos inclusive schools, a cycle is already in full swing. The force, in the long run, may dunk more Lagosians below the poverty line.

*Some of the names are changed to avoid victimization