The 2025 edition of the Resource Centre for the Blind’s Family Forum has brought up genetic transmission of disabilities, and the need to check it as PWDs start families. The policy framework for this lacks certainty, though.

A session of telling personal stories of mental and emotional impact of disability on families and caregivers initiated the deliberation. Lagos JONAPWD chairman Lukman Salami, his vice chairman Yemisi Isado, and a blind cluster member, Isiaka Adebayo, took turns to tell their stories.

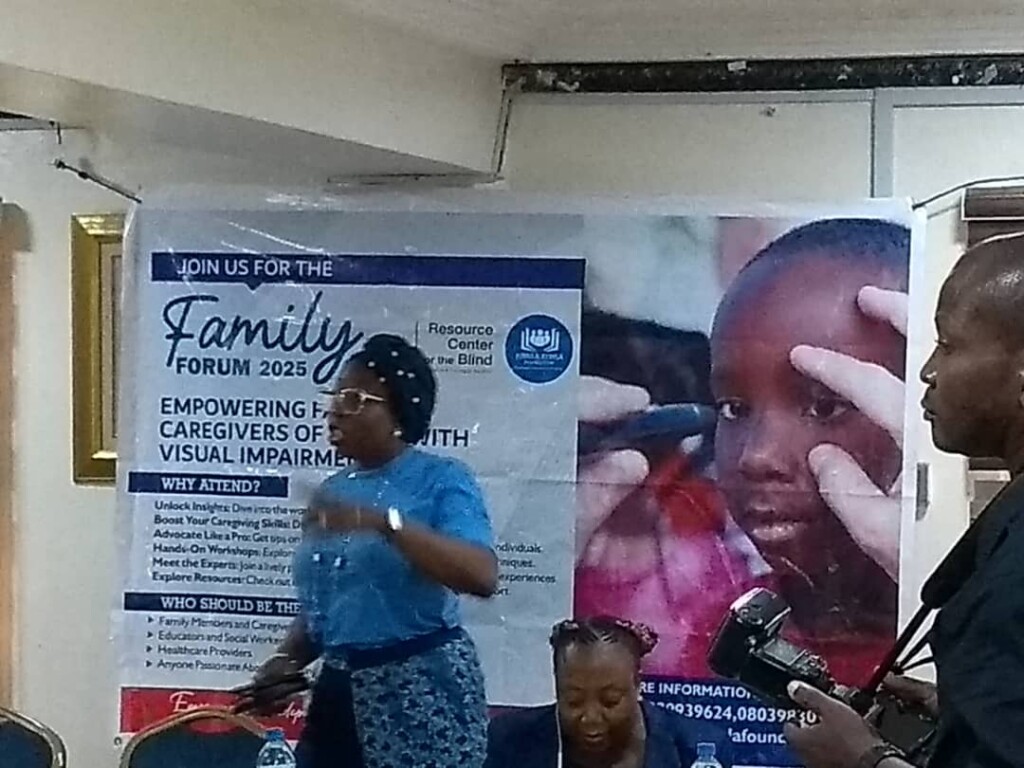

An invited guest Francis Azu, chief medical officer, DFO Hospital, Lagos, then made a point of scientific and technological interventions in softening disability impact. And the event moderator Kemi Odusanya brought the issue back later for emphasis, heightening the audience interest inside the LCCI Gallery Hall, Alausa, on April 24.

For Isiaka Adebayo, one of the six visually impaired siblings in a family of eight, the impact presents differently.

According to the political science graduate, their parents supported them growing up. The children also had the good fortune of being among the first set of pupils that graduated from Pacelli School for Blind Children, a Catholic organization in Lagos.

“Among the six of us are lawyer and other professionals. I can even say we are more brilliant than the remaining two without visual impairments,” the father of four and publisher said. “But, unfortunately, every one of us is having one blind child in his or her family.”

His wife had breathed a sigh of relief—that her own family escaped the disability—before the fourth child, a son, presented with it. “She now feels disappointed,” Adebayo said while seeking clarification on the scientific intervention that can stop the trend.

As a doctor and disability-focused philanthropist, Frank particularly understands Adebayo’s predicament. And for families who may not have gone far in passing their disabilities down to generations, the doctor suggested genetic recoding, four-monthly medical check-ups, pre-natal testing of embryos, among other measures.

“When an unborn baby is discovered to have been affected genetically, senior doctors in the hospital can meet, and agree to advise the intending parents to terminate such pregnancy,” Frank said.

The doctors’ role here is only advisory, though he said there are laws guiding that sort of intervention in Nigeria. The Nigerian National Health Act makes no provision for this kind of intervention. And the Criminal Code (South), in sections 228, 229, and 230, which reflect similar provisions of the Penal Code (North) in section 232 and 233, criminalises abortions. There is an exemption, though: Section 236 permits abortion when it is necessary to “save the life of the mother”.

Legal debates and precedents have pushed forward the frontiers of interpretation of an abortion saving lives—to include accommodating ‘mental health of the mother’.

A genetically disabled unborn baby may threaten no life; but with the burden of care and attention it demands after birth, such baby likely has a grip on the mother’s (or family’s) mental health, medical practitioners may argue.

The vagueness of both codes doesn’t guarantee an easy way out for couples with genetic disabilities seeking medical intervention to halt paasing of disabilities down their bloodlines. But the Discrimination Act 2018, in clear terms, prohibits discrimination against PWDs, including in marriage.

Many Nigerian PWDs, however, have problem having spouses that have no disabilities. Marriage within clusters offers a solution, but raises the odds of perpetuating disabilities in some relationships.

Certain conditions are basically genetic. Frank cited the little people, for instance. They may not be aware of this, and how marrying partners like them cements the generational transmission of their disability.

“The government can’t prevent PWDs from falling in love with whomever they choose,” the doctor told ER. “All they need is more enlightenment and awareness.”

The situation puts many in the community on tenterhooks—more so when mental health gets into the mix. “Persons with disability must get into relationships for the sake of their mental health,” Frank said in his speech earlier. But the easiest route to that lies in intra-cluster marriage, which comes with its own price.

Salami believes the odds are not sure, though. “Intra-cluster marriage is not a conclusive proof of genetic transmission of disability,” he told ER. “I know a lot of blind persons that got married to one another, and their children are okay.”

Yet, as Frank and other guests observed, the families and caregivers of the three who shared their stories demonstrated a lot of resilience. It never matters the disability is only genetic in one case.

Salami has no such gene as his counterpart does. But his story highlighted the impact his birth family’s frustration could have had on him when his father was about to farm him out to an Islamic cleric for apprenticeship. “It was the only thing my family thought I could become when I lost my sight to measles at eight,” the lawyer said.

For three years, an uncle doubted Salami was studying law at UNILAG. And with a second-class upper and a successful completion of his law-school programme, he also grappled with distrust within his profession. “I never stated my disability in my application anytime I applied back then,” he said. So a senior lawyer of a chamber fishing for bright sparks from the law school couldn’t believe him when they met for a job interview. He dismissed Salami with a cash gift of N100,000. “I told him I only came for a job interview, and I left,” Salami recalled. He got a job in Lagos’ justice ministry later. “As fate would have it, we met in court, and I floored him.”

Yemisi had her own parents to confront when she lost her hearing early in life, and her family found themselves at a loss for what to do with a deaf girl. She told them about the special education college in Oyo, and her father gave his nod. “Just to try any alternative to begging,” the businesswoman told the audience. She graduated, and started a fish farm. She went further to learn catering.

But family problem, in another dimension, still dogged her. The mother of one endured domestic violence in her marriage until she had to walk away to protect whatever remained of her mental health.

“In all, I know where I am going. I might not be there yet. It’s just a matter of time,” she said.

The forum also featured presentations focusing on other issues, including education, career development, and self-advocacy in creating inclusive workplaces.

Among the speakers were Razak Adekoya, Sightsavers’ global technical advisor; Dolapo Agbede, JONAPWD (national) project director; Temitayo Ayinla-Omotola, the centre’s director; and representatives from LASODA.