Climate change turns the heat on Nigerians with albinism, endangers their lives and livelihoods

Gbenga Ogundare

No fewer than 24 persons with albinism will have died in Nigeria by the end of 2024. The annual figure the Albinism Association of Nigeria (AAN) puts out reckoned with only reported fatalities. Many more of the six million persons with albinism (PWAs) across the nation go through stages of ultra-violet ray-induced skin cancers in the lead up to some of the deaths.

“As you know, the sun is our No.1 enemy,” Bisi Bamishe, AAN’s president, told ER, noting the onslaught of the ultraviolet ray on PWAs.

Nigeria has been spending billions of its Eco Fund to mitigate climate change impact on the environment. At least N39.6 billion from federal allocation flowed their between June 2023 and June 2024. Not much of that has benefited directly the PWAs who need to build resilience under the impact. And the omission is a matter of policy. That leaves the the community with no alternative. They have to brave this jeopardy—as long as they rise up, go out, and make a living each day.

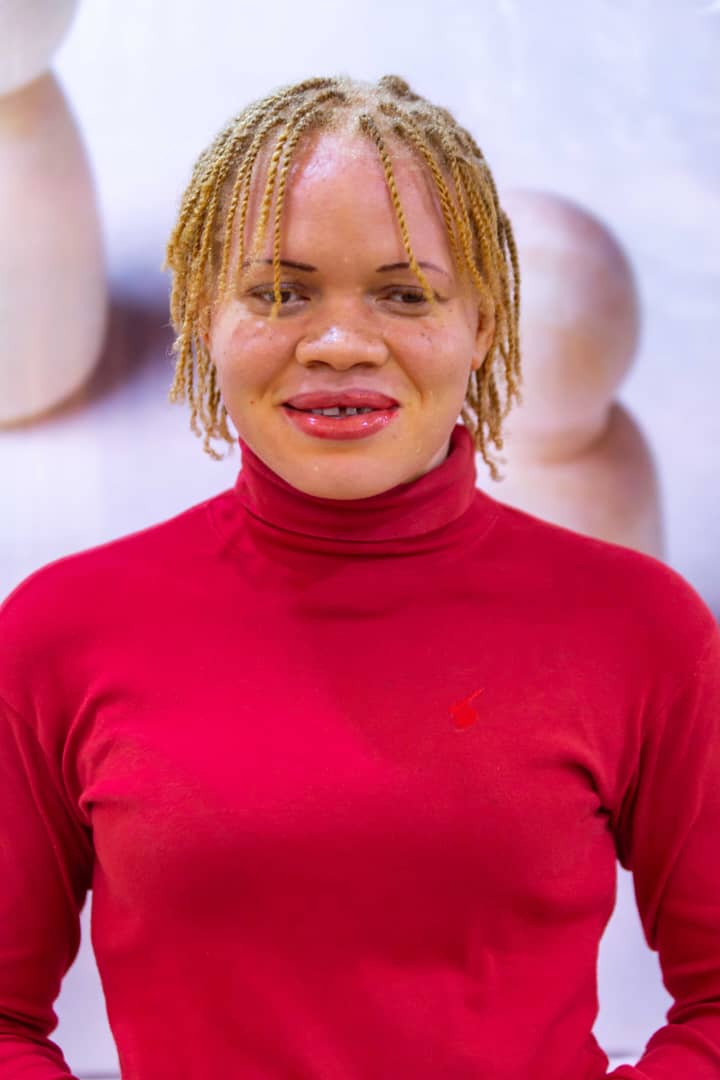

So on December 1, Victoria Adesanya woke up at dawn to say a very difficult prayer—that the sun never rise from the east. For a marketer with albinism whose melanin-deficient skin now tells tales of cancerous lesions and freckles, her daily desperate wish is understandable.

The ultraviolet index value hit 10.0753 around mid-day later that day, as measured by UV Index. That was about the average of the 10 days ER monitored ultra-violet radiation in Lagos (and Ibadan which had over 9.0) between November 30 and December 12. Experts say figures above 8 pose risk for certain shades of complexion—riskier for Victoria’s.

“I am not able to go out in the day anymore because of the damages the sun has done to my skin already,” she said.

Victoria, Omobolaji Kalejaiye, Uche Callister, Sarah Agbeye, Oluwatoyin Adekankun, and Adesewa Adejare also dodge the sun while others are hard at work. It is all they can do.

Bamishe said people must still go out to look for survival. “But for our members, going out to buy and sell now is very terrible.”

Everywhere is hotter than ever, Victoria and Omobolaji admitted to ER. Climate change spikes extreme temperature in a hotspot like Nigeria, especially Lagos, Abuja, and Ibadan. To worsen it, vegetation has become a rarity in those capital cities. Their endless terraces of concrete, tarmac, and heat-absorbing roofing soak up heat blazing down through the compromised protection of ozone layer, and make a hell of the surroundings.

Callister

The UV Index, which measures the intensity of UV radiation, ranges between 7 and 9 in summertime in Germany, as high as 8 in the UK, and 7 in Finland. From the UV radiation index analysis on Nigeria, using ten years daily data extracted from the archive of the Ozone Monitoring Instrument (OMI), the result showed that solar UV radiation is at its peak at local noon time from January 2010 to December 2019. According to a team of researchers from Covenant University and Lagos State University, the peak value 10 was observed in the month of November, December, January, February, and March. The study further showed that the ultraviolet index over Nigeria's varies from high to extreme (i.e., from the southern to the northern regions

Besides suffering the impact of global warming, PWAs also now watch their wealth, their sources of living melting. It can’t be otherwise where a government fails to provide an environment for citizens whose health conditions deserve special needs to live. Such citizens face deprivation of their rights to also participate equally with others in making a living.

Nigeria has ratified the UN Charter on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities which defines disability in light of interactions between health and environment. A tome of other laws and conventions, including the Discrimination Act 2019, the Paris Agreement, and the Kyoto Accord, also recognize such interplay. They urge signatories to help PWDs build resilience under this inclement climate. It is a matter of rights and social justice.

But Nigeria hasn’t lived up to those conventions’ demands. Maybe intercontinental accords like those lose their seriousness at home. The ministry of education that formulated the National Policy on Albinism could have had its own motivation in 2012. The policy guiding principles generally entrench the rights of PwAs to education, health, and socio-cultural integration. It specifically highlights their economic empowerment in its Principles 4. Implemented, the economic plan—with its employment quota, viable career options, and entrepreneurial skilling—could improve the resilience of Victoria, Sarah and others. They won’t have reason to risk ultra-violet ray burns and cancer.

It matters little that the policy is not climate-focused.

After all, none of Nigeria’s climate policies has disability components. The Nationally Determined Contributions to carbon reduction, for instance, lacks disability inclusion.

Various social protection programmes also assure Victoria and others of social insurance and labour market interventions. These could help them absorb social shocks the climate change impact generates.

However, to most of the women, all these provisions are a mirage. “Once they see you as an albino they will stylishly discharge you,” said Sarah.

ER sought comments from the disability community on the albinism policy’s Principle 4 implementation. Jack Ekpelle, founder of The Albino Foundation, and Jaiyeola Fatungase of The Albino Network Association, two of the policy drafters, didn’t respond to the request.

Bamishe, however, confirmed none of the policy’s principles has been implemented since its last review in 2019.

“We have gone to the ministry of education in Abuja, had meeting with the stakeholders so the policy will be implemented,” she said.

In her view, the National Commission for Persons with Disability “has not really done much”—compared to states.

She recognized Lagos’ effort which allows AAN’s members to participate in its empowerment programmes for PWDs

Even then, the kind of economic empowerment the state handed the PwAs is of little use. Intersectionality is missing.

“If you ask us to do a trade that will make us sit out in the open—there is no way we can do that—because of the ultraviolet rays,” she said. “Tailoring is also a bit hard because of threading. We are classified as PWDs because of our low vision.”

AAN'S President Bamishe

Hundreds of PWAs that had the luck to have been so empowered have not experienced much change in their productivity. Not in Nigeria’s current economy.

The inflation rate stands at 34 percent now. This makes it not the best of times to lag behind in the hustles and bustles of Nigeria’s economy—just for the color of one’s skin.

Sarah had wanted to be anything but petty trader. When her sight started blurring in secondary school, she managed it, and adapted as much as she could. All that wasn’t enough, though. “During WAEC I failed three times so I give up on going to school,” she told ER. What she lives on now doesn’t even occupy her enough. “If I had not had to stay indoors as much as possible, I could have been trading till about 4pm, and be making between N10,000 and N20,000 daily,” she said. Yet three kids, her mum, and, on occasions, her husband lean on her for their upkeep.

Callister is still at school, pushing some kind of e-commerce on the side. She loses five of her man hours—from 10 am to 4pm—to sun-dodging daily. Her drop-shipping business could have benefitted more from longer legwork, and fetched her a higher income.

Nursing was Adesewa’s first love. Now a farmer, she has to work randomly on her farm to avoid scalding her skin. “My income would have been N300,000 monthly as a farmer,” she said. The maximum she makes monthly now hovers above N15,000. No fewer than ten persons she supports depend on that.

In those 10 days ER monitored for the albino women interviewed, the average man-hours they could safely work was 4 daily. That amounts to 28 hours a week—or about 4 days in the month of December. In a whole year, Victoria could safely work in the open for 48 days. (Of course the women took their chances, and pushed the limits.)

Yet they all emphasized how unequal the opportunity compares with others, and how the inequality tells on their standards of living. How much they grapple with it equally depends on their current state of disabilities.

“I now have to strip myself naked while in the room and stay under the shower every other hour to keep my body cool and prevent skin redness and blisters,” Victoria said. The knick-knacks she sold in her mom-n-pop business remained unattended during that period. She can’t even go out any longer to look for clients. “The sun has already presented me with cancer that requires an urgent surgery.”

Omobolaji has to visit several marketplaces to source materials for the clients who patronize her fabric enterprise. For her, no two ways around daring the sun most times. “The most important thing is that I use my protective gears. And most times, I look out for a shade place to relax for some minutes,” she told ER.

Sarah, too, grapples with a multitude of freckles on her hands. She comes out early in the morning to display her goods in front of the house and go back inside before the sun comes out. A few customers will come knocking at her door. “But majority will go elsewhere if they can't find me outside,” she said. “I lose sales, really, but that is better than the heat that will damage my skin further with cancer."

Callister is not spared the blitz from the heat either, despite moving her skin care trade online. The entrepreneur and student of hospitality management at the Yaba College of technology told ER the extreme heat has become a threat to her skin and business altogether.

“I noticed that sunshine from 12pm - 3pm is extremely hot, so I try to avoid it by getting to the market on time and then return before 12pm,” she said.

Even at that, she must decked herself up in some protective gears and apply a specially made cream on her skin, in addition to wearing a sunscreen, and shielding herself with a large umbrella. “Later in the evening by 4pm, I deliver the goods to wherever the customer wants.”

Adesewa can’t go to farm in the sun, either—for fear of skin redness and other threats. But when going to farm becomes unavoidable, she shrouds herself in some special-purpose sun prevention apparatus.

“I usually wear my boots, put on long sleeve with hat in as much I can prevent sun from penetrating to my skin,” she said.

For Adekankun, she would prefer to work at her poultry before the sun rises. As early as 6am to 11am, she told ER. And evening, too, from 5pm to 7pm.

That’s a lot of worries for these women. Especially as Nigeria’s healthcare system offers PWAs little or no safeguards from the health spin-offs of UV radiation. So all their protective effort comes at a cost, which actually affects their balance sheets.

Efudix cream which helps to safeguard them from skin troubles has remained out of reach. “Not much people patronize me these days. It becomes unaffordable for me,” Callister said.

According to Victoria, a 40 gram jar of Efudix now sells for N150,000 or N100,000 for a 20-gramme jar. “I have seen many people with albinism who couldn’t afford to buy these essential products because we don’t have jobs,” she said.

The International Labour Organisation stated in one of its reports on Just Transition that climate change is going to remove, modify, substitute 18 million jobs worldwide, and create six million more. That indicates the employment crisis Victoria painted is real. And it will continue to bait the PWAs to hazard their health to make ends meet.

In Nigeria, available disability laws, with their job quotas and other employment provisions, have yet to guarantee PWDs equal opportunities in the labour market. With the government skewing climate policies against this vulnerable population, a segment like the PWAs have to brace up for tough times ahead.